Central Texas looks for ways to balance population growth with future water supplies

By Lizzie Jespersen, Fri., Aug. 29, 2014

|

| Photo by John Anderson |

Flash forward about 60 years. In his narrative chronicle of the Fifties Texas drought of record, The Time It Never Rained, author Elmer Kelton recalled, "Ranchers watched waterholes recede to brown puddles of mud that their livestock would not touch. They watched the rank weeds shrivel as the west wind relentlessly sought them out and smothered them with its hot breath. They watched the grass slowly lose its green, then curl and fire up like dying cornstalks."

Today, another 60 years later, drought continues to be a recurring theme in Texas. But in booming Austin and the surrounding areas of Central Texas, the ongoing drought is not one of classic Western imagery that is simultaneously wretched and romantic.

The portrait of our drought reveals a city whose population influx could threaten to overtake its water supply; it shows lakeside residents and businesses closing their doors to the beached buoys and docks that used to beckon customers by boat; and it tells the story of homes and lives ravaged by wildfire.

Race Against Time

Texas is no stranger to drought – its history is a saga of drought and recovery, a pattern that is indigenous to the state and would run its course even without a human footprint. And despite climate change, we are not certainly seeing a long-term spike in drought conditions. According to State Climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon, there are no clear indications in the trend of Texas' drought patterns that the severity and frequency of drought has increased – in fact, he said, there were more droughts prior to 1970. But there's one key difference between pre-Seventies Central Texas and today: us. With a rapidly expanding population and no signs of deceleration in sight, Austin's demand for water has become a race against time."Water supply contains a combo of [meteorological conditions] and population," Nielsen-Gammon said. "If this had taken place in 1990, we probably would have had much better water supply than we have now. ... In terms of per capita, with water availability we are basically back to where we were in the Sixties."

Central Texas' current drought has earned a ranking of one of the 10 worst droughts in the last 500 years, and based on the past four years has likely also claimed the title of the second-worst drought on record, said Nielsen-Gammon.

|

Brian Hunt of the Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer

Conservation District measures spring flow just below

Barton Springs Pool. Photo by Jana Birchum

|

While residents play a part in the drought through a combination of greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change, and through the added demands that plumbing, irrigation, and daily living place on the water supply, the biggest influence on Central Texas drought is beyond human control. Natural variations in climate temperature and behavior have existed cyclically since the beginning of time. Experts have analyzed our current drought through the lens of such climate patterns – according to Nielsen-Gammon, the overlap of two specific climate trends, called Pacific Decadal Oscillation and Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, is largely responsible – but even those of us without a doctorate can see proof of a larger climate change cycle in the form of ice ages and, on a smaller level, Texas' unshakable tendency toward drought.

The Human Scale

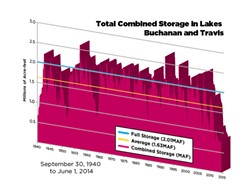

The concept that the occurrence of drought is a natural and inextricable part of this world, and Texas in particular, is an important one. For the layman, however, an understanding of drought comes down to one thing: water availability. While temperature variations and precipitation may be largely at the hands of some greater climatic or even geological power, the human demand for water does affect the availability of what is not an infinitely available resource. A comprehension of where water comes from, and where it is going, is especially valuable on a regional and local level. Two different bodies largely supply Central Texas water: the Highland Lakes and Edwards Aquifer. The Highland Lakes – Buchanan, Inks, Lady Bird, Marble Falls, Travis, and Austin – were formed by a series of dams and are managed by the LCRA, which contracts 424,602 acre-feet of water from the lakes to 3,984 customers (as of May 1, 2014). Lake Travis provides the city of Austin with its water supply for utilities and construction, and has been the most visibly drained by recent drought conditions of all the Highland Lakes. Lake Travis currently holds 393,264 acre-feet of water – just 35% of its storage level when full.Getting By and Making Do

John Hofmann, whose title at the Lower Colorado River Authority is executive vice president of water, said the agency is involved in many conservation projects for these lakes, with a full-time conservation staff that works on developing ways to address the issue. Over the years, LCRA has granted several hundred thousand dollars to conservation projects, and has held irrigation evaluation sessions and worked with stakeholders such as the Home Builders Association and golf courses to coordinate conservation efforts. "We basically manage water for the drought," Hofmann said. "If you're not in drought, you're looking for the next one."Still, critics of LCRA, from the grassroots level to the Legislature, fault the agency for not responding sooner, and for failing to conserve the region's water supply at the height of the drought in 2011, when it released enormous amounts of water downstream to rice farmers. Many of these downstream farmers have since been cut off from the Highland Lakes water supply.

The Edwards Aquifer is a groundwater resource that re-entered a Stage II Alarm Drought on Aug. 18, after a brief water conservation period that began June 27, according to the Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer Conservation District, which regulates groundwater pumping. The district, which manages both the Edwards and Trinity aquifers, has walked the line between drought and conservation periods for several years. BSEACD Education Coordinator Robin Havens Gary said these fluctuations are simply the nature of aquifers.

"Central Texas has a lot of what people call periods of drought interrupted by periodic floods, and that's what is reflected by water levels," Gary said. "It's not something that has just happened. Droughts have been occurring in our area for a long time. The drought declarations allow us to have a coordinated water conservation plan, so everyone can get on board and help conserve and preserve the water that we have until it starts raining again, and then the aquifer will get replenished."

For many aquifers, it takes hundreds or even thousands of years for

rainwater to reach and recharge them. By comparison, water is able to

make its way into Edwards Aquifer very quickly, making it a special case

in Texas. Still, Edwards Aquifer and the BSEACD supply 60,000 people

throughout Hays, Travis, and Caldwell counties, who rely on the aquifer

as their sole source of water, according to Gary. Many of these peoples'

wells have been dry for years.For the past two years, Artie Berne has

had water delivered to his home in unincorporated Travis County, just

outside of Lakeway, where he lives with his wife and two pets. Ever

since his well's water table dried out and fell below the pump's intake

level, a water truck has brought 2,000-gallon water deliveries to

Berne's home every five to six weeks. Berne said going from free water

to paid deliveries has made him conserve much more in his day-to-day

life. "Now I'm hypersensitive about water," Berne said. "I go to the gym

and I'm super sensitive, and these people are leaving the water on

while they shave. I'm like, water!"

For many aquifers, it takes hundreds or even thousands of years for

rainwater to reach and recharge them. By comparison, water is able to

make its way into Edwards Aquifer very quickly, making it a special case

in Texas. Still, Edwards Aquifer and the BSEACD supply 60,000 people

throughout Hays, Travis, and Caldwell counties, who rely on the aquifer

as their sole source of water, according to Gary. Many of these peoples'

wells have been dry for years.For the past two years, Artie Berne has

had water delivered to his home in unincorporated Travis County, just

outside of Lakeway, where he lives with his wife and two pets. Ever

since his well's water table dried out and fell below the pump's intake

level, a water truck has brought 2,000-gallon water deliveries to

Berne's home every five to six weeks. Berne said going from free water

to paid deliveries has made him conserve much more in his day-to-day

life. "Now I'm hypersensitive about water," Berne said. "I go to the gym

and I'm super sensitive, and these people are leaving the water on

while they shave. I'm like, water!"Berne and his wife have also proactively conserved water by ripping out their front lawn in favor of a xeriscape of plants and mulch. Still, even for other neighboring residents with similar lawn plans, making a water delivery last for six weeks is impossible. Some of Berne's neighbors who rely on water for families of four or more need the 2,000-gallon deliveries on a weekly basis – an expense that, at $85 a tank, quickly adds up. Families in the area who have run out of water (or funds) before the next scheduled delivery have had to go without showers and clean clothes, making do until their next refill. Others whose wells have yet to run dry have begun installing tanks, fearing that it won't be long until aquifer water will recede from their own wells as well. Many of these families rely on water from Edwards Aquifer, while some draw from nearby aquifers such as the Trinity.

Edwards Aquifer "is subject to a lot of water withdrawals," Gary said. "We certainly have more pumping than we would see in the Fifties, and that's our management challenge."

During the most recent "conservation period," the Aquifer District called for a 10% reduction in water use across the board, while mandatory water use restrictions were lifted. "We realize that this is one of the highest demand times for water," Gary had said during the conservation period. "And while the aquifer – the trigger points have been met [to declare it out of a groundwater drought] – we're not in a water-full situation, so this water conservation period allows us to keep that water conservation message front and center, because that's what everybody needs to be doing right now."

Now that the aquifer has officially receded back into drought, water use restrictions have been reinstated; all parties holding water use permits must reduce their pumpage by 20%.

Finding Strategies

Though recent rains briefly alleviated the severity of Central Texas' groundwater drought, Gary said one of the biggest challenges to further replenishment is that ground and surface waters are connected. "What rolls off at one point replenishes the aquifer at another, and what comes out of groundwater replenishes the surface water at another," Gary said. With groundwater and surface water – in this case, Edwards Aquifer and the Highland Lakes – so interdependent, it's hard to imagine any major restoration occurring within the aquifer while Austin's lakes are still enduring a drought rivaling that of the Fifties.In hopes of removing some of the burden from the Highland Lakes, the Austin Water Resource Planning Task Force recently made several recommendations for alternative water sources and management approaches in its July 10 report. The short-term task force, which consisted of 11 members appointed by Mayor Lee Leffingwell, City Council members, and environmental-interest commissions, identified "recommended strategies for study ... that could potentially serve as sources of water within a long-term framework or could provide other benefits over both short and long periods," according to the memorandum. These strategies include applying a biodegradable powder to the lake surfaces to reduce evaporation, seasonally changing Lake Austin's levels to capture runoff rather than allowing it to spill downstream, contracting with new groundwater suppliers to obtain additional water sources, and desalination of brackish water zones of the Edwards Aquifer.

The ultimate effectiveness of these methods is uncertain. Contracting with new groundwater suppliers is perhaps the least onerous of the potential undertakings, though a question remains whether other prospective groundwater sources are healthy enough to withstand the added burden of Austin Water Utility customers. Desalination has become a topic of interest across Texas, and has had some success in El Paso, home to the largest desalination plant in the United States. However, Texas Water Foundation's Executive Director Carole Baker said desalination presents a solution, but also a problem. "People always default to desalination," she said. "We could always do that, but there are a couple of issues. The cost goes up, and the energy you need to clean up that process uses a lot of water."

Fighting for conservation measures at the state level, voters in 2013 overwhelmingly passed a ballot measure to allocate $2 billion from Texas' so-called Rainy Day Fund to create a loan program for water-related projects – primarily pipelines and reservoirs – to help ensure Texas' water future; 20% of the water fund program is designated for conservation projects, while another 10% will be delegated to agricultural water conservation projects.

Changing the Mindset

In the midst of Central Texas' showdown between inevitable drought and population growth, and a desperate need for new solutions like the ones discussed by the Austin Water Resource Planning Task Force, one message has remained consistently in the forefront: conserve. Conserve now, and conserve often. Baker and the Texas Water Foundation are a part of the growing effort to emphasize conservation as one of the few drought-related measures that has few drawbacks and can be implemented directly, widely, and immediately."Of course the drought seems to just be ongoing and probably will be, is what we're sort of anticipating," Baker said. "I think one of the main things we are working on right now is trying to educate the public on this situation so they don't think every time we have rain, everything is back to normal. ... The key thing is to look at how water is so connected to so many things; to try to change the mindset, because that will change behavior. It's looking at how water is linked to the economy, to the environment, to communities."

Texas Water Foundation's particular brand of educating has been largely through multiday bus tours, during which they take legislators and decision makers from the Capitol on a tour of the state for a firsthand look at regional water challenges. The foundation has also held conferences over the past several years to bring conservation issues to the forefront – something that has been especially effective, Baker said. "We're actually in a pretty good place right now," she added. "Conservation and efficiency are really a large part of the conversation these days, and we've worked a long time to get it to that point where people are asking, 'What can we do?'"

Just because water conservation has entered the platform of statewide discussion doesn't mean activists and educators don't have their work cut out for them. Baker said that while many of their education and policy efforts have focused on legislators and water utility companies, their biggest battle now is with the general public. "If you talk about saving energy, people are great at that, but when it comes to talking about water, not so much," Baker said. "These issues are so different across the state, but all of them are focused on the fact that if we are fixin' to double our population over the next 10 years, at the end of the day, the best thing we can do is to learn how to conserve and use water efficiently."

The Next Generation

Some conservation activists have decided to focus on educating a different audience entirely. Austin-based nonprofit Colorado River Alliance holds field trips for young students on the land outside of LCRA headquarters in West Austin, where the students can peer from atop the overlook to see the Tom Miller Dam and the lakes that are a part of the water supply for much of Central Texas. Sarah Richards, Colorado River Alliance executive director, said when students discover exactly where their water comes from, and where it's going from there, it creates a greater conviction of personal responsibility for water usage and conservation."Knowledge is so critical – that they know how much we're using, and also that they know the source of their drinking water," she said. "When people can't point at it and say, 'That's where my drinking water is coming from,' it's hard for them to know to conserve."

Even parents and teachers have pulled Colorado River Alliance members aside during field trips to say that they had no idea about the water's uses or how much water a typical family uses. The alliance's biggest focus, however, has been on children. "It's important to see that our current leadership and decisionmakers are aware and have a strong knowledge of water resources, but it's just as important that our future leaders are aware," Richards said.

Some of the conservation tips are so simple, but can go a long way toward conservation: Turn off the tap while brushing your teeth and save three gallons of water. Shorten showers and save up to 150 gallons of water per month. Fix leaky faucets. Bathe pets in outdoor areas that need watering (while adhering to outdoor watering restrictions). Use rain barrels to harvest rainwater from gutters.

According to Baker, learning how to properly work residential irrigation systems is one of the biggest ways in which residents can contribute to conservation efforts. Not only does this ensure not overwatering lawns, but it also includes only cultivating native plants and grasses that can be irrigated through rainwater.

In searching for answers in how to match Central Texas' valuable water resources to its prodigious growth, one thing can be agreed upon: No matter how much of the drought is out of human hands, this is an issue that should – and will – remain at the forefront for all of Texas, whether it is in a home or during legislative meetings.

"I think the biggest [message we need to emphasize] is: Whether we're in a time of drought or not, this is a shared resource, whether it's shared across the community, or whether we're sharing it with the environment," Richards said. "That just becomes more important when there's less water available."

No comments:

Post a Comment